Chapter 3 INVESTIGATION INTO MEDITATION

Preparation For Meditation

The Four Body Postures

Clothing

Posture

Kneeling Benches

The Head

Using Chairs

The Hands

The Apperceptive Gaze

Note of Warning

Exercise 2: Working with Your Threshold of Discomfort

Tranquillisation

Exercise 3: Body Affects the Mind

Distractions

Dealing with Distractions

Know Thy Posture

The Simple Return, A Meditation Strategy

Equanimity

"Monks, I know not of any other single thing so intractable as the untamed mind. The untamed mind is indeed a thing intractable.

Gradual Sayings (Anguttara Nikaya),

The Book of the Ones, Ch. IV

Translated by F. L. Woodward

Meditation should be scientifically approached, by reproducing the same practice conditions. The meditator must do their best to keep these conditions constant. The difficult variables will be in the mind. The mind can only be observed, even if the meditation becomes a watch-mind-clutter meditation, so be it. If you do that, pat yourself on the back. Well done. If you are expecting bliss, I tell you now, forget it. Awareness reveals all you need to face, if you remain present. Squaring up to yourself is the easiest thing to do, but the hardest to maintain.

Preparation For Meditation

The Buddha taught the bhikkhus15 to train in meditation using one of four basic postures: standing, walking, sitting, and reclining. These are collectively known as the Satipaṭṭhāna (satipaṭṭhānaṃ singular).

The most popular posture for meditation is the seated position. But there is more to remaining seated for prolonged periods than is apparent, and finding one’s optimum posture can only be discovered with practice. Some people are supple, and will have little problem sitting cross-legged for the duration of a meditation, but most people will require hours of trial and error before the most sustainable posture is found.

A rule of thumb when meditating is that tight clothing is out and baggy clothing is in. This is because the muscles of the body must be allowed to stretch and settle.

It is meditation hall etiquette to move quietly, and not to disturb others, so soft fabrics that don’t rustle are preferable. If you find you have to move, do so in slow motion, to help minimise noise. Moving in slow motion also helps preserve one’s own tranquillity.

A spare blanket can be useful during the cold months of the year.

Reducing discomfort will go a long way to reducing mental activity. A stable and comfortable posture is needed, and one that suits one’s body shape. If your posture is moving, even slightly, your subconscious will pick it up and ferry that into awareness. It has to, that’s its job. The mind does not like doing nothing. It is multifaceted so it can interface mind, body and awareness. Even though you sleep, it is never fully switched off. It can’t be switched off. Awareness is crucial for survival. A fundamental activity of the psycho-physical mechanism is to nag and snag the imaginative faculties. This often manifests as daydreaming, and difficulty staying attentive. If your posture becomes painful, it will result in a stream of distractions. That’s the mind doing its job, getting you to address your bodily requirements. The distractions are not your fault! Note: you are never endeavouring to stop the mind by force, even in meditation. But by maintaining what I call the apperceptive gaze, and only rarely using force, you will start to transcend distractions and leave them behind.

Because body shapes differ, there is no such thing as one posture suits all. Each meditator has to go through a process of discovering his optimum posture, and any supports that may be needed. Soft cushions may initially feel comfortable, but after a few minutes of sitting, the muscles around the hips and knees will stretch. Whilst muscles compress and stretch, ligaments do not, and so the initial comfort gained from cushioning may turn to discomfort after several minutes. Just as athletes must warm up before an event, the meditator also goes through an initial period of bodily settling down. The Buddha refers to this as ‘tranquilising the bodily formations (MN118:16-18).’

Figure 3 Spine and Head

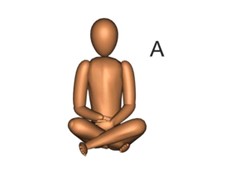

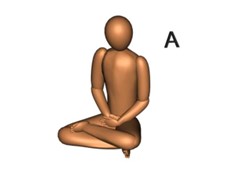

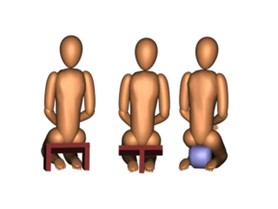

Figure 3a is a very natural way of sitting cross-legged, with the lower legs resting on the feet. The problem with this is that the higher the knees are the more one has to lean forward to counter forces pulling the torso backwards. Also, the force of gravity pressing the legs down onto the feet will cause discomfort in the feet. A remedy for this is posture 3b, in which the heel of one foot is placed into the groin area, while the heel of the other foot touches the shin of the other leg. This does create an asymmetrical body posture, about which a physiotherapist would, no doubt, have something to say, if only this position were used frequently. It is a good idea then to alternate the footing between sits.

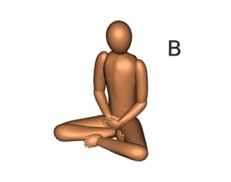

Figure 4 shows how knee supports can be used. Purpose made meditation cushions are available, and come shaped variously as rectangles, rounds or wedges. Polystyrene foam is versatile but it compresses very easily. Tightly rolled up towels secured with tape make good supports.

Figure 3 Spine and Head

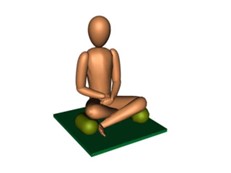

Some meditators don’t use any support and rely on the Half Lotus (5a) or Full Lotus (5b).

Figure 5 Feet Positions

In the half lotus, the calf and foot of one leg rests upon the other calf and foot of the other leg.

In the full lotus, both feet rest upon the opposite thigh, while both knees rest on the floor. It is a minority of meditators that use this.

Some meditators sit astraddle cushions, or a wooden kneeling bench.

Figure 6 Kneeling

Optimising posture requires angling the spine to make the lightest possible work of supporting the head. The head is heavy, and has to be gravitationally balanced so that its weight is taken, as much as is possible, by the neck and spinal column, thereby minimising muscular effort. The top half of the body will resemble a soldier on parade. He too has to remain still for long durations. He is taught to straighten the back, hold his head high, and tuck in the chin. This posture is held for the full duration of the sit. It is the posture the meditator returns to time and time again, when he realises he has slouched. Slouching is serious, as it inhibits breathing, which induces sleep.

Maintaining awareness of posture is an excellent meditation technique in of itself. If every other moment of the meditation is spent checking one’s posture, it’s still a meditation, even if it feels demanding. The muscular discomfort that comes with making a little extra effort also helps stave off sleepiness.

Never feel dismayed if you feel your meditations are going nowhere. Nowhere results in voidness, and “only Voidness is unsurpassable” (MN121:12-13).

It does not matter that not everyone can make like a soldier on parade. What matters is consistency of posture, and standing guard.

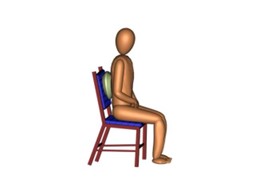

A chair can be used, especially when sitting cross-legged is not viable. The upper body is treated the same as sitting on the floor, or in a chair, or kneeling. First, make the spine reasonably straight and vertical, with the base of the spine near or touching the back of the chair. Because the back of some chairs slope, a cushion between the back of the chair and your spine might help. It is not there to take any real weight from the body, as the cushion will compress with time. It is there to give feedback on your balance (fig.7). Even micro changes in posture will be picked up by the mind and impinge on consciousness, and manifest as needless mental activity, unless you can diagnose what’s happening.

If support is needed for the back, be mindful of the long-held habit of getting as comfortable as possible. If you get too comfortable, you will fall asleep. A little muscular discomfort is better than too much comfort. The back and neck muscles very quickly strengthen with daily practice.

Figure 7 Chair Position

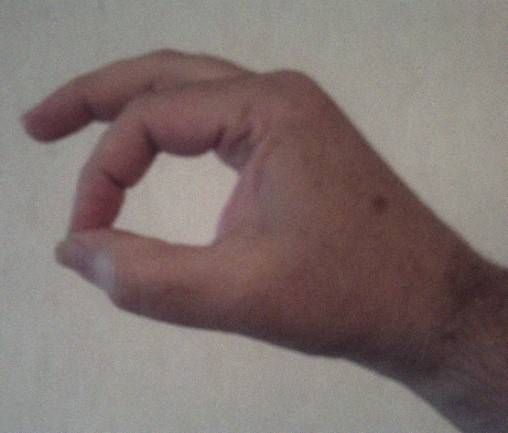

Occasionally, a meditator is seen adopting something called a mudra. There are half a dozen or more mudras. A commonly seen one is where the tip of a finger touches the tip of a thumb. Images of the Buddha often show him meditating with a mudra, although mudras are not prescribed in the Canon. If he actually did this then his reason was practical, as is characteristic of his teachings. I suggest a mudra could be used as a feedback mechanism to monitor how still one has remained during meditation. Just as a marksman uses the cross-hairs on his rifle sights to target a fixed spot, so too the meditator can use a mudra as a sighting mechanism, to fix a spot on the ground (see figure 8). The meditator can then compare his posture at the start of the meditation with his posture at the end, to see how far he has moved.

Figure 8 Mudra

This sighting-mechanism explanation attaches a great deal of importance to remaining millimetre-still. Indeed, simply remaining as still as possible for 20 minutes or more, is an excellent meditation, as a still body has a stilling effect on the mind. Thus, an image of a Buddha, holding a mudra, is a snapshot in lesson how to meditate.

Holding a mudra without any support for an extended period, is demanding, as it causes serious muscular stress, which excites the imagination. Thus, the meditator must pay meticulous attention to the contents of the mind and body, moment-by-moment, using the apperceptive gaze to preclude the imagination from streaming. A mudra calls for a very intense, here-and-now experience, however, mudras are not at all necessary.

The hands may be rested on the lap. Placing the hands further forward, towards the knees, shifts some bodyweight forward, and helps counter any tendency to fall backwards. Those with sensitive joints may find that this brings extra weight for the knees to carry, which may stress them, and because there is nothing supporting the arms, the elbow joints can also become stressed. Sitting on a cushion, so the knees rest lower, also counters the tendency to fall backwards. It is up to the individual to find their most sustainable posture.

The Apperceptive Gaze

The apperceptive gaze is the kernel of what the Pali Canon calls Vipassanā. Vipassanā includes not only seated meditation but bodily actions. If you learn anything about Vipassanā learn, one uses just enough energy as is necessary, “…just to the extent necessary for knowledge and awareness (DN22:2).

I use the word gaze, because it is an extended act of apperception, as distinct from just fleeting glimpses of internal focus (See Chapter 2, The Technique of Apperception). As one perceives the external world, one apperceives the internal world. As one spectates the external world, one introspects the internal world, using the same, in-the-moment intelligence. What some call the “I am” awareness.

So, what happens during meditation? The answer is nothing. It feels like a useless thing to do, as it is taking you nowhere, and this is offensive to the mundane mind, as it flies in the face of your survival instinct. The simple act of apperception immediately precludes freedom of the audio and visual faculties to blindly drive us or passively entertain us, which is the usual, every day, mind. Apperception is the antidote for a streaming imagination.

Is it not true, you don’t have to have the next thought?

By precluding the discursive mind, the meditator is skilfully descending into nowhere, succumbing to Voidness (See Chapter 20, subtitle, Descent into Voidness). The apperceptive gaze is a very easy thing to do but difficult to maintain. Use the least amount of effort required. Nothing can rush the descent into voidness, but at the same time don’t let anyone tell you it takes life-times, or even one life-time.

The body and mind are inextricably linked. Together they impinge on consciousness. Consciousness is the ‘I am’ awareness. This “I am” awareness is what Sāriputta meant by the eye of wisdom.

Sāriputta: Friend, one understands a state that can be known with the eye of wisdom.

MahāKoṭṭhita: Friend, what is the purpose of wisdom?

Sāriputta: The purpose of wisdom, friend, is direct knowledge, its purpose is full understanding, its purpose is abandoning.

MN 43:10-12

But what is it that is abandoned, we well ask? The Buddha said, “These are … the taints that should be abandoned by seeing (MN2:11).

We can contemplate what is meant by ‘abandoned by seeing’ by looking at the etymology of the word Vipassanā. It is a Buddhist hybridized Sanskrit (Pali) word. It is a compound word made up of at least two Pali words: vi 116 + pass 117 = apart, asunder + see. It means to split from, by seeing. If direct knowledge, that is one’s own experience, is relied upon, the term Vipassanā and what I call the apperceptive gaze are synonymous. Pressing the pause button in the mind brings about the split from being driven by the mind to detachment from being driven.

Ordinarily, hunger, thirst, tiredness, threats, … will manifest in your awareness as distractions, or daydreaming, or an inability to focus. The more disturbed the body is, the more effort will be required to maintain the apperceptive gaze. At times, a disquieted mind is best dealt with using suppression. Yes, effort is a gross mental condition, and therefore preclusive of more refined levels of consciousness, but a gross mind state can also be wilfully dismissed in an instant. One’s body-mind condition determines what just enough energy amounts to. The more tranquil the mind, the subtler the effort should be. This is how consciousness is purified. Apperception is the process of applying one’s finger to the pause button of the discursive mind, which is spring-loaded and in everyday life, shoots back up the moment you release your finger.

Note of Warning ![]()

If you are a house dweller, and you practise Vipassanā, that is apply the apperceptive gaze moment by moment in your work-a-day life (something the Buddha did not teach laity to do), focusing inwardly while the world necessitates you focus outwards, will make you feel divided. It will also attract every narcissist, sociopath, and psychopath in the vicinity. These phenomena are why I say: a dedicated effort requires a dedicated environment. And even in a dedicated environment, not everyone will have the same sensibilities.

Investigating Posture ![]()

Personalising posture is a foundational step for anyone wishing to explore meditation over an extended period. It should be borne in mind that no posture is totally comfortable all the time, and so it is important you have satisfied the mind that you have explored, and found, your optimally adjusted posture. We can all transcend some discomfort, but how much? The following exercise is dedicated to finding your threshold of discomfort 118for a chosen posture, so you can hold it for at least 20 minutes. The threshold of discomfort occurs when the meditator decides discomfort, physical or mental, is beyond tolerance. A meditation can take 20 minutes for the mind and body to settle down and reach tranquillity (see below). If you can do this, consider yourself competent in meditation. Meditation retreats often adopt repeated 50-minute sits, with breaks in between.

Exercise 2: Working with Your Threshold of Discomfort ![]()

Adopt your chosen posture, and hold it for at least 20 minutes, no more than 50. Breathe freely but otherwise remain as still as possible. Move only if you feel you really have to.

Do this at least once a day for a week or more.

* * *

Over a period of a week, you will find that some pains will come and go, and sometimes for no apparent reason. But some will be stubborn. The idea is to note the stubborn ones, and find remedies for them if you think they will be problematic. The outcome will be a posture you can hold without moving, for at least 20 minutes.

Instinct says we should start off as comfortable as possible, but this is not always the best strategy. The posture and supports to adopt are the ones most amenable in the middle and the end of the sit. Of least concern, is feeling comfortable at the beginning. This is somewhat counter intuitive, but it should be remembered that cushions compress, muscles stretch, while ligaments are unyielding. Until your body and any soft supports stop moving, you cannot ascertain what your optimised posture and supports will be. Puffing up pillows at the beginning of each sit is not a good idea. A flattened pillow at the end of the sit is how it should be at the start.

If your chosen posture turns out to be slightly uncomfortable at the beginning, that’s OK. If you still finish a sit feeling unbearably uncomfortable after a week of practicing, then explore other postures and supports. If you can sit motionless for 20 minutes or more, without having to adjust your posture, even while feeling uncomfortable, you have a viable posture, and, you can meditate. It’s about finding the middle ground. This does not exclude people from meditation with neurological conditions that can’t stay motionless. The endeavour is to bring about the stilling of the mind.

The Buddha described the settling down phase at the beginning of meditation as ‘tranquillising the bodily formations’ (MN118:16-18). A meditator who does not factor the tranquillisation period into his understanding of meditation, risks feeling defeated in the initial stages. Patience truly is a virtue in the first several minutes of meditation.

The tranquillisation process is worth underlining. A runner does not step onto the running track and immediately start running his maximum. He warms up his body gradually, with exercises. So too, the meditator needs time to warm up. It takes a meditator at least several minutes from a cold start to relax into his posture. Stretching exercises beforehand can help. Whilst muscular stiffness can be stretched away, and weak and aching muscles will grow in strength, joint pain does not necessarily fade. Joint pain is sharp, and anything longer than a mere twinge, should not be endured. Definitely explore supports, stretching exercises and tweaking the posture. As we get older, remaining motionless becomes physically more testing, as muscle tone won’t be what it once was. But this should not put anyone off meditation. Even the Buddha took rest periods between meditations in his old age (DN16.2.25).

If you have to move in meditation do so in slow motion, while maintaining your gaze. This will minimise exciting the mind. Anyone with a nervous system that makes physical stillness impossible, is still able to meditate. Indeed, walking meditation was prescribed by the Buddha. The Venerable Sāriputta (not the Buddha) advised ailing householder Nakulapitā to accept the view: “Even though I am afflicted in body, my mind will be unafflicted (SN III 22:1).”

Any physical discomfort that is cognised, has impinged on the mind, and is technically called a mind object (see Table 6 Internal and External Bases). Mind objects are transient, unlike the Eye of Wisdom, as Sāriputta called it. The eye of wisdom is the intelligence that is aware, even when asleep, awake, and moving between lives (given that there is something to cognise).

Although not endorsed by Buddhist teachings, some say the eye of wisdom, consciousness, the I am awareness is eternal and the real you. There is a discussion on the Buddhist perspective on this point in the Introduction, see Eternal - The Deathless.

Every obstacle in meditation is a stepping stone to self-transcendence.

Tranquillisation

Exercise 2 was about finding your threshold of discomfort, so you are able to maintain a posture for at least 20 minutes. Exercise three is the same as exercise two, except this time, the idea is to notice how physical discomfort excites involuntary mental activity (mind objects). At the end of this exercise the meditator is to reflect, and compare the condition of the mind and body at the beginning of the sit, with the mind and body at the end. If this exercise is done earnestly, it will become clear in the meditator’s mind how the relative discomfort at the beginning of a sit, agitates the mind, compared with the comfort and mental tranquillity at the end. That’s it, that’s the point of this exercise; to make this mind-body phenomenon clear and to plant it in your long-term memory. The reader should not think I am teaching the obvious and skip over this. It is only by squaring up to this phenomenon, at the most intimate, moment-by-moment level that it can become more than stating the obvious.

Exercise 3: Body Affects the Mind

Adopt a posture, which you can sustain for at least 20 minutes, no more than 50. Breathe freely but otherwise remain as still as possible. With the eyes closed, apperceive the mind and body.

* * *

You already understand how your consciousness is affected by hunger, tiredness, biscuit crumbs in bed. Remedying these issues is usually taken in your stride. But in meditation, remedying distractions is subtler. The mind is typically unwieldy at the beginning of meditation. This phenomenon does not go away with experience. It is tackled, as always, with patient application of the apperceptive gaze, or a nimittaṃ, of which the classic one is following the breath. When the distractions come a calling, don’t feel annoyed because they don’t instantly go away as you want them to. It’s not your fault. It’s what the mind and body do, especially when you bring discipline to bare upon them. The tranquilisation stage cannot be speeded up, as that is tantamount to wanting, and that is a hindrance to meditation. The correct wisdom to apply to mind objects is, ‘This is not mine, this I am not, this is not my self.’ (MN28:6-7). But, it is somewhat your fault if you regret losing focus, as you’ve allowed the mind to snag you twice. Similarly, you don’t think the correct wisdom, you come to learn it, and know it.

The apperceptive gaze will halt the imaginative faculty instantaneously, but not so much physical sensations. Becoming absorbed in what you are doing can sometimes bring about transcendence of physical discomfort. Technically, absorption is a jhanic state called rapture. We will study this shortly.

In Buddhist psychology, anything that enters awareness is a mind object. Mind objects can be prevented from turning into daydreaming by applying the apperceptive gaze. That’s what makes it ever useful. Use skill; not will, whenever you can.

Distractions

Focusing on a task, becomes more of a challenge when discomfort (dukha) becomes more serious. Whatever the origin, stress can complicate the ability to focus, and manifest as daydreaming, as well as night dreaming. When the body feels sweet, day/night dreaming is sweet. Conversely, when the body feels discomfort, the mind can blow up a storm, and one’s mentation will reflect that. Find the off button, and thoroughly contemplate mind and body for tiredness, hunger, thirst, threats, any physical, and emotional discomfort. Having identified a need, deal with it. Watch how the mind calms down when you have correctly identified and have attended to your need(s). This protocol is a noble contemplation and is useful whenever you start to feel restless. It is always worth implementing before making decisions and apportioning blame, as it minimises the extremes of sentiment and excitement that can bleed over onto our contemplation of people and things.

It is possible to focus too intensely during meditation. It can cause breathing apnoea where the breathing becomes shallow or may stop, leading to a reduction of oxygen in the blood, which then causes drowsiness and dreaming. Taking a few deep breaths during periods when the mind is particularly distracted can be helpful. Do this as quietly as possible. Try breathing out longer than you breathe in, say, count 4 in, and count 6 out, or whatever relaxes you most.

In addition to muscle ache and joint pain, neuropathies such as pins-and-needles, tingling and numbness, can be distracting. Some palliative action might include moving a limb slightly to improve circulation. If you have to adjust your posture, do so in slow motion. This will help preserve the tranquillity you are developing.

Reviewing one’s diet in the light of inflammation-causing foods is always worth investigating. Nutrition theory is not always consistent, but eating less processed foods is generally recommended. Some people are better with vegetarian food than others. The Buddha did not preclude eating meat, presumably because beggars cannot be choosers. Do not underestimate the power of hunger to disturb the mind, fasting with equanimity is truly noble. We will look at what the Buddha had to say about diet towards the end of the book.

Sometimes physical discomfort can be so pronounced it has to be worked with directly. That is, the discomfort and thoughts arising, by necessity, become the focus of attention. As always, the idea being to not let a mind object become mind activity. The discomfort will try to wrest your stillness from your control. The earnest meditator should be on any mind object instantaneously, aware of the discomfort while not letting the mind move. If the discomfort lasts more than a few moments, adjust your posture, in slow motion, keeping your finger on the off button.

You are not trying to stop the discomfort; trying is doing something and that disturbs the mind. You are staying in the stillness of the apperceptive gaze, the I consciousness; the nothing that is something. The curious thing is, the more successful you are at this, the more likely you are to be unaffected by discomfort.

The same approach applies to any pleasure felt during meditation. Many will be surprised, even disappointed, to read that pleasant feelings are not the goal of meditation. Treat pleasant feelings with the same impersonal manner as discomfort, by applying the apperceptive gaze. This treats all sensations with the same equanimity; neither welcoming them nor pushing them away.

After several days on a meditation retreat, and the mind throwing at you every piece of concern, daydream, paranoia that it can, in order to wrest control from you, you’ll know when you’ve got through the thick of it, as you will start having identical thoughts, and even pains, occurring at the same time during sits. Take this as a good sign. It means the mind is running out of effective ammunition to distract you. Like a feral horse being tamed, which is unwieldy out of survival instinct, it finally acquiesces, as it realises the horse tamer isn’t going to hurt it. After all, your relatively feral mind has never surrendered to voidness before. It’s not used to being forced into redundancy. How does it know meditation won’t kill you, or it, after all, its job is to keep you alive? Repetition of identical thoughts at this juncture of meditation are easy to let go of, and indicate that you can descend into voidness at will, or more accurately by skill. Of course, you don’t look for, or wait for, repeat-thoughts; they will find you, if they do.

Meditation retreats are rare opportunities to take meditation to deeper levels than is possible at home. It would be remis not to make the best of the opportunity for lack of preparation. One thing meditation retreats test to breaking point is posture and resolve. Being unsure about where to put one’s effort is a recipe for despondency and failure. Without the above foundational experience, a novice will likely capitulate to exasperation. Note, you are busy doing nothing: you are going nowhere: the mind hates it: you can handle it.

The Simple Return, A Meditation Strategy ![]()

Promise yourself that while meditating, the moment you realise you have lost your focus, you will immediately make a simple return to your apperceptive gaze, or nimittaṃ if you are using one.

* * *

What is a simple return? Once it is realised focus has been lost, immediately return it to one’s meditation, without pausing for one more thought. A simple return means no loitering on the feeling associated with the last thought before returning to your gaze or nimittaṃ (object of attention). A simple return means what it says.

It is a misunderstanding to think that by feeling negative about losing focus, you, the meditator, is somehow storing up positive energy to use against the distraction the next time around, as an athlete might when readying to take on the opposition. Such purportedly positive feelings and thoughts are another imagining to be avoided. They amount to getting snagged on the mind for a second time. If you lose focus, make a simple return, as best you can. Never indulge feelings of exasperation at having lost focus. As a meditator you are going to lose focus countless times, and so thinking and feeling exasperation when you lose it, trains the mind to think and feel exasperation every time you lose it. That’s a lot of potential exasperation, which clearly is not healthy for you. Once you’ve spotted the loss of the apperceptive gaze, make the simplest return you can. Leave no quarter of the mind for regret. Clean away any negative feelings by maintaining your gaze. Clearly this calls for a wakeful mind.

Equanimity ![]()

You now have some practical insights on posture, tranquilisation, apperceptive gaze and the simple return. The practice of the apperceptive gaze is the practice of equanimity. To face anything with equanimity is to be mindful and can be rightly called the noblest of all spiritual practices. If pure equanimity cannot be preserved throughout discomfort and pleasure, then the renunciant’s endeavour is to be mindful of that. This is not a failed condition! Good work is still being done, as the meditator is seeing things as they are.

Before we study the meditation teachings in the Pali Canon, just a quick note to the urbanite meditator. When in an urban environment, the mundane world must have first call on your time and energy. Never allow yourself to fall into the trap of feeling negative because circumstances are not ideal, as that’s another source of potential stress. We will look at how the urbanite can engage a meditation practice later in the book.

A lot of people reading this book are light-workers, that is, mediums, healers, star-seeds, empaths … . Meditation will enhance the skills of these psychic types. However, the descent into voidness requires these skills are ignored, as they are distractions. We will look at psychic skills when we look into miracles.